Kinship

Develop an understanding of First Nations, Métis and Inuit perspectives of kinship with one another and the universe.

To begin, select a category from the menu.

Kinship systems are as complex and diverse as the people and communities who practise them. Encompassing societal values and spiritual beliefs within a land-based framework, kinship systems help to maintain traditional ways of life, assure the care of and responsibility for the elderly and young, and determine the sharing of work and the distribution of food. In essence, kinship ensures the clan’s survival. Although some kinship terms have been replaced with English terms, the extended family network remains important to Indigenous peoples and continues to apply in contemporary life. In this part of the journey, you are invited to examine how the Cree kinship system follows the concept of “the whole community raises the child.”

Sarah has just sent report cards home and requested parent/teacher interviews.

She is concerned to learn that Naomi’s aunt will attend this interview instead of her mother. Sarah’s principal, Ken, tells Sarah that Naomi’s mother is away, working towards a bachelor’s degree.

Ken shows Sarah a school-based form, signed by Naomi’s parents, indicating that Naomi’s aunts are to have parental access when they are not available. Ken explains that this document was designed in consultation with Cree community members in order to facilitate good communication between teachers and parents. In the northern Cree family system, of which Naomi is a part, grandmothers and aunts may play a significant role in the raising of children.

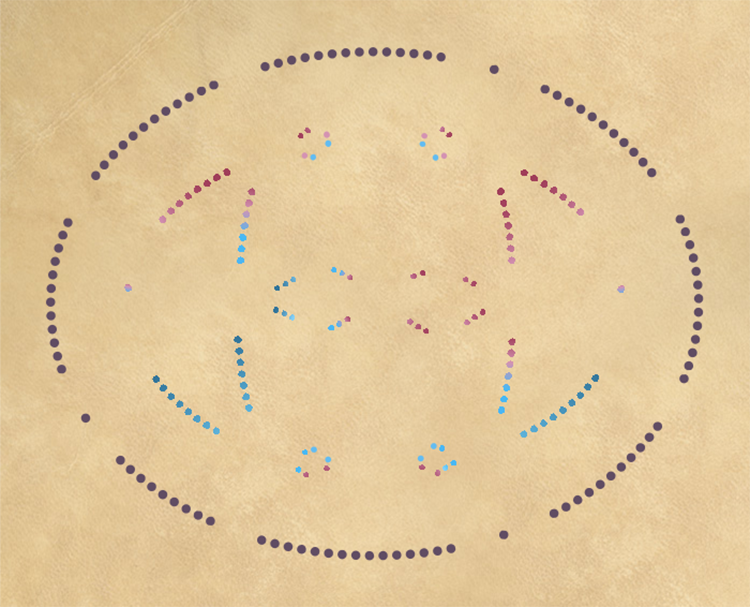

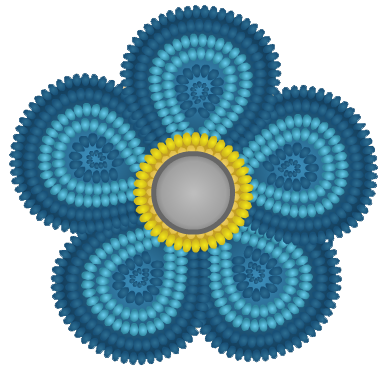

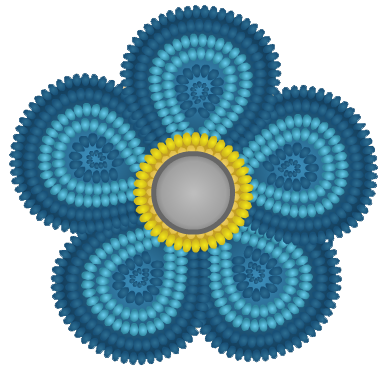

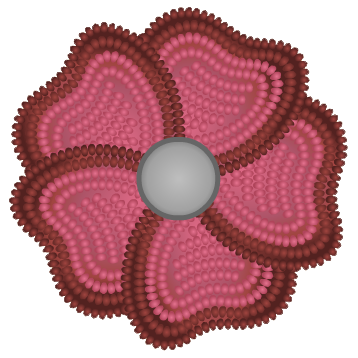

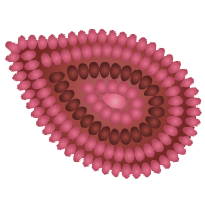

Intrigued, Sarah asks Naomi and her aunt to help her understand the Cree kinship system in greater detail. They bring in a beadwork design to help explain the system. In Naomi’s matrilineal ancestry, the Cree women have long favoured flower designs for their beadwork patterns. Representational of intergenerational ties and regional artistic practice, the flowering vine helps to express the intricacy, richness and fluidity of family relationships within the Cree kinship model.

Me

I call myself nîya.

My mother and father call me nitânis.

My younger sisters and brothers call me nimis.

Brothers

I call my older brother nistēs.

I call my younger brother nisīmis.

My mother and father call their son nikosis.

Father

I call my father nohtâwiy.

Grandfather

My maternal and paternal grandfathers and all their brothers (great uncles) on both sides are all called nimosôm.

Great-grandparents

All my maternal and paternal great-grandmothers and great-grandfathers and their brothers and sisters on both sides are called nitaniskotâpan or câpân (this term translates to “my extended ancestral line” or “link in an extended chain”).

They also call me and all of their great-grandchildren, câpân.

Paternal Uncle

My father’s brothers are like my own father. I call them by a similar name: nōhcâwîs, which means “Little Father.”

Male Cousin (Parallel)

My family regards the older sons of my maternal aunts and paternal uncles as an older brother. My brother and I call them nistēs.

My family regards the younger sons of my maternal aunts and paternal uncles as a younger brother. My brother and I call them nisîmis.

Grandmother

My maternal and paternal grandmother and all their sisters (great aunts) on both sides are all called nohkom.

Paternal Aunt

I call my father's sisters nisikos which also means “mother-in-law.”

Grandfather

My maternal and paternal grandfathers and all their brothers (great uncles) on both sides are all called nimosôm.

Grandmother

My maternal and paternal grandmother and all their sisters (great aunts) on both sides are all called nohkom.

Great-grandparents

All my maternal and paternal great-grandmothers and great-grandfathers and their brothers and sisters on both sides are called nitaniskotâpan or câpân (this term translates to “my extended ancestral line” or “link in an extended chain”).

They also call me and all of their great-grandchildren, câpân.

Mother

I call my mother nikâwiy.

Sisters

I call my older sister nimis.

I call my younger sister nisīmis.

My mother and father call their daughter nitânis.

Maternal Uncle

I call my mother's brothers nisis, which also means “father-in-law.”

Maternal Aunt

My mother's sisters are like my own mother. I call them by a similar name: nikâwis, which means “Little Mother.”

Female cousin (Parallel)

I regard the older daughters of my maternal aunts and paternal uncles as an older sister. I call them nimis.

My family regards the younger daughters of my maternal aunts and paternal uncles as a younger sister. My brother and I call them nisîmis, which is a more formal term. We have a more formal relationship.

Male Cousin (Cross)

I consider the sons of my paternal aunts and maternal uncles as close cousins. I call them nîtim.

My brother calls those boy cousins nîscâhs.

Female Cousin (Cross)

I consider the daughters of my paternal aunts and maternal uncles as close cousins. I call them nicâhkos, which also means "sister-in-law." We have a less formal, "joking" relationship.

My brother calls those girl cousins nîtim.

Sisters

I call my older sister nimis.

I call my younger sister nisīmis.

My mother and father call their daughter nitânis.

Reflection Statement

Through kinship and language, cultural practices are transmitted from one generation to another. Founded on sharing and reciprocity, family and kinship systems function to ensure family preservation, community connectedness and the continuation of cultural heritage.

How might knowledge of family and kinship networks improve your success in working with First Nations, Métis and Inuit students in your district?

Theresa Strawberry explains her culture’s kinship system with a story about her granddaughter.

The speakers in these interviews talk about about the deep, sacred ties of kinship that extend to the human family and beyond to all of nature.

Select a video.

Alvine Mountain Horse | Kainai | Blood Tribe

Alvine Mountain Horse, who has taught the Blackfoot language for many years, provides kinship terms in Blackfoot with English subtitles.

Wilton Goodstriker | Kainai | Blood Tribe

Elder Wilton Goodstriker, Kainai First Nation, provides an overview of Blackfoot kinship systems.

Larry Daniels | Nakoda | Bearspaw Band, Stoney Nakoda Nation

Larry Daniels, Nakoda speaker, shares his perspective on kinship.

English adaptation: When you are Nakoda/Stoney and you go back home, you know where you came from. You know who your relatives are. The Nakoda/Stoney language is an important base for knowing what kinship means, including an understanding of our kinship with nature, with the mountains.

Theresa Strawberry | Saulteaux | O’Chiese First Nation

Saulteaux educator and grandmother, Theresa Strawberry, explains her culture’s kinship system with a story about her granddaughter‘s understanding that she has two mothers and two fathers.

Marge Friedel | Métis Nation of Alberta Region 4 | Urban Elder

Métis Elder Marge Friedel shares memories of growing up at Lac Ste. Anne, which is called Spirit Lake by the Cree because the spirit of the water has healing powers. She describes a strong cultural upbringing in a big extended family untouched by residential schools.

While Marge Friedel passed in 2011, we are privileged and honoured to still have her words to share.

John Janvier | Dene Suliné | Cold Lake First Nations

John Janvier, Dene Suliné from Cold Lake First Nations, shares stories of how his ancestors lived in extended family groups before contact with Europeans.

A Relationship Model of Kinship

Through complex and diverse kinship systems, Indigenous cultural practices are transmitted from one generation to another. Founded in sharing and reciprocity, kinship systems ensure family preservation, community connectedness and transmission of culture. In this video Narcisse Blood comments on parts of Leonard Bastien’s presentation on Blackfoot societies at the Social Studies Summer Institute in 2007.

While Narcisse Blood passed in 2015, we are privileged and honoured to still have his words to share.

Select a resource type from the list.

Web Links

While some First Nations, Métis and Inuit experts have recommended these web links, they are not authorized by Alberta Education.

Kinship Group. Alberta Online Encyclopedia

This web page presents kinship as part of relational law that connects social, cosmic and spiritual domains. Other topics include family responsibilities, respect, kinship terms, and redress and judgment.

Documents

While some First Nations, Métis and Inuit experts have recommended these web links, they are not authorized by Alberta Education.

School, Family and Community. Our Words, Our Ways. Alberta Education

Schools can be welcoming environments for all parents, extended family and community members, all of whom share the responsibility for educating children. This excerpt from Our Words, Our Ways suggests ways to create welcoming environments, including protocols for relationships with Elders.

Traditional Social Organization. Aboriginal Perspectives

Traditional Indigenous social organizations are obligated to provide education and mutual support to their members. This excerpt from Aboriginal Perspectives (Aboriginal Studies 10) introduces extended families and clans, societies, roles and responsibilities, education and socialization, and methods for resolving conflicts.

Select a video from the list.

Wahkohtowin: The Relationship between Cree People and Natural Law

This video deals with subject matter that some viewers may find controversial, stirring deep emotions. Viewers on all sides of the issues are encouraged to engage in open discussion in order to truly understand the situation.

Bearpaw Media Productions of Native Counselling Services produced this video in 2008 with funding from the Alberta Law Foundation.