Understanding the Acquisition of English as an Additional Language

|

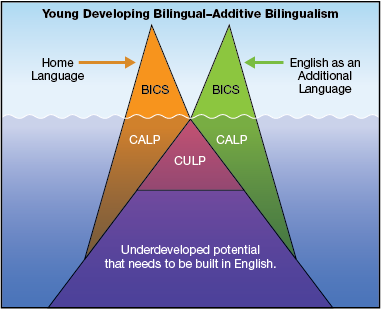

← Back to Using Iceberg Models Scenario 1: Young Learners Adding EnglishShreya immigrated to Canada from India with her parents when she was three years old. Shreya is now nine years old. She has made many English-speaking friends at school and in her neighborhood. Shreya and her parents speak Hindi at home. They have Hindi-speaking relatives, friends, and community members that they socialize with. Shreya’s family also has Hindi magazines, newspapers, and books at home as well as access to some Hindi films and TV shows on DVD. They also watch Canadian TV shows and listen to local English-language radio stations in the car. They use some popular computer and phone apps to stay in touch with relatives in India. Shreya recently started visiting the local public library and borrows books on a regular basis, including some in Hindi at her reading level. Shreya’s proficiency in Hindi continued to grow while she was developing English proficiency. Now, Shreya’s English proficiency is about the same as her Canadian-born English-speaking peers. She developed her social and academic language (BICSBICS (basic interpersonal communicative skills): simple, functional language for communicating basic needs, ideas, and opinions and engaging in everyday conversations in informal social situations and CALPCALP (cognitive academic language proficiency): language required to understand and communicate about abstract concepts and accomplish a wide-range of cognitively demanding academic tasks, including reading textbooks, writing essays, and doing research) in both languages to about the same degree in both Hindi and English. She can express herself equally well in both languages about many topics. Shreya’s profile is commonly described as Young Developing Bilingual—Additive Bilingualism because she has added a language (English) without losing a language (Hindi).  Additive bilingualism describes a student who learns (or adds) a new language while maintaining the first or home languagehome language: the dominant language that a student uses at home to communicate with family members. This diagram illustrates both languages developing at the same time in a young child who is born into a bilingual home or is exposed to two languages simultaneously. Both languages are developing in the social and academic areas. CULP CULP (common underlying language proficiency) the language knowledge and skills that students develop as they learn one language that they can then use to help them learn other languages is accessed simultaneously, and these children can often go back and forth between the two languages easily. As these students get older, and if their proficiency in both languages continues to develop, CALP will grow significantly larger on both sides of the diagram. As well, underdeveloped potential will gradually shrink while CULP expands. Both languages would need to be developed continuously throughout the child’s education for the child to maintain bilingualism. Implications for the Instruction of English Language Learners These English language learners tend to sound relatively proficient in English based on their social language (BICS). They will, however, need to be supported in building their CALP to develop the level of language proficiency necessary for academic success. These students need explicit language instruction and language-learning strategies to develop their relatively shallow common underlying language proficiency. |