Understanding the Acquisition of English as an Additional Language

|

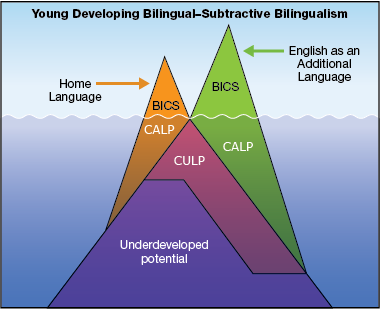

← Back to Using Iceberg Models Scenario 2: Young Learners Losing Their Home LanguageCarlos immigrated to Canada from Central America with his sister and mother when he was six years old. The family has Spanish-speaking relatives and friends, and Spanish is spoken at home all the time. Carlos spoke only Spanish when he started school in Alberta. He is friendly and outgoing and has made many English-speaking friends at school, on his community soccer team, and in his neighborhood. Carlos is now 12 years old. His English proficiency now is about the same as his Canadian-born English-speaking peers. He has well-developed social (BICSBICS (basic interpersonal communicative skills): simple, functional language for communicating basic needs, ideas, and opinions and engaging in everyday conversations in informal social situations) and academic (CALPCALP (cognitive academic language proficiency): language required to understand and communicate about abstract concepts and accomplish a wide-range of cognitively demanding academic tasks, including reading textbooks, writing essays, and doing research) language. Although his mother continues to speak to him and his sister in Spanish at home, Carlos now mostly answers in English. As well, he and his sister speak only in English to each other. The only books written in Spanish that Carlos was exposed to are children’s books that he has now outgrown. Carlos never learned to read Spanish, but he does recognize many written words. Over the past six years, Carlos has gradually lost much of his ability to converse in Spanish and prefers not to speak Spanish at all. At this point, if he had to, he would probably still be able to talk about a limited range of everyday topics using simple Spanish. Carlos’s mother worries that he will not be able to communicate with many of his relatives in the future and that he will not pass his home languagehome language: the dominant language that a student uses at home to communicate with family members on to his children. Carlos’s profile is commonly described as Young Developing Bilingual—Subtractive Bilingualism because he is losing the ability to use one language (Spanish) while acquiring another language (English). In Carlos’s case, instead of adding proficiency in English to his proficiency in Spanish, English is replacing Spanish.  Subtractive bilingualism describes a student who learns a new language but gradually loses the ability to communicate in the first or home language. This diagram illustrates a young child first exposed to one language and then exposed socially and academically to English. BICS and/or CALP in the home language were not maintained or developed further, and most of the time the child uses English. Initially, the child relied upon his or her home language to learn English. After a time, however, the child may have used CULP CULP (common underlying language proficiency) the language knowledge and skills that students develop as they learn one language that they can then use to help them learn other languages developed through the learning of English to support the home language. The child may grow being unable to read or write in the home language. He or she may still be able to understand the home language when spoken to but then respond in English. Implications for the Instruction of English Language Learners English language learners who are at risk of becoming subtractive bilinguals are difficult to identify in a classroom setting. Their teachers readily see the progress they make in developing their English language proficiency but may not see the gradual erosion of the home language. Subtractive bilingualism has a profound and overwhelmingly negative impact on students and their families. The loss of the home language may prevent generations within the same family from communicating with each other, and it may negatively impact a student’s sense of cultural and personal identity. As well, the erosion of the home language makes the learning of English as an additional language more challenging than it would be if the student could draw upon a well-developed home language to learn English. Many factors beyond the influence of the school contribute to subtractive bilingualism, but schools can support the home languages and cultures of their students. See Encouraging the Use of Home Languages. |